nycBigCityLit.com the rivers of it, abridged

Fiction

What I Owe the Thief

David Francis

Yes, I know his name, I've said it enough (though not recently), I doubt I ever will forget it. Not only that but I've had it said to me: What happened to _______? Many persons know him as a character and he is the kind of butterfly that flits on male and female…flowers…known by other characters alike, a geometrical multiplication in a city so important and large. Which also makes it possible — almost — to hide. Yet when two victims of a theft get to talking the jig is up. Especially in a place all three frequented: the place is no more. It got hot in a personal way because of this comparing of notes. The second victim induced doubt, certainty in the first. This led to the disappearance of the — more than alleged — thief.

He was known to float from sofa to couch, to bounce around the boroughs. No fixed abode is an understatement. The second victim, a no-nonsense printer of about forty, with a grave countenance with a hint of menace, was his host for a while. The first victim had him over and had gone to the bathroom, as he recounted, remembering, only to later notice the phantom of a fifty dollar bill in his dresser drawer. Drunk, he convinced himself that he had not seen what he saw, had not possessed what was his, or had lost a valuable in the tiny bedroom he rented from the apartment holder. The second victim heard this with streetwise resignation. He had lost, forever, a ring which had sentimental value. "Oh, weally," he lisped cockney. His name was Tony. He had grown up in London and admitted to having been a "scrapper" in his youth, the youth that temporarily belonged to the thief. Tony was a person you could talk to in a bar, who had a pint, minded his business and went on his way. A regular but not a drag. Like every non-native New Yorker worth knowing, he guarded his privacy. He had no pretense of artistry or entitlement.

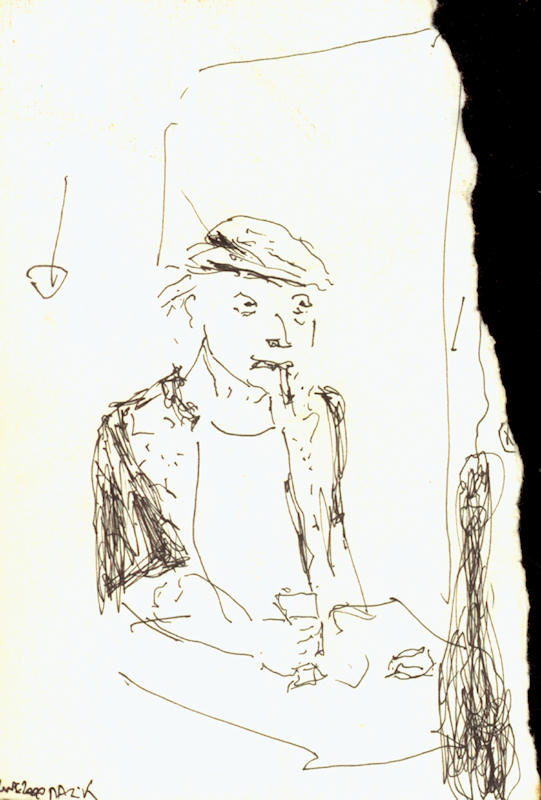

The thief, however, was a mother-spoiled, fatherless child of the streets who had acted (he said it was a year since he appeared in a television commercial). A hard day was spent occasionally, he claimed, in auditions. But most of the time was eked out in scoring drugs and mooching and sleeping — in public. How did he do this — make a life out of it? He was blessed with charm. Nature or nurture? Both. He had very good manners acquired from an upbringing in the diplomatic community and several private schools. Smooth manners stood out among the slackers, art school dropouts, potheads, scammers and dole duffers. Besides, he was cute. He seemed lazily good-natured. Yet he had that bearing. He gave you his full attention from drooping brown eyes punctuated by a pleasant giggle. He had the rapid speech of an African, a self-deprecating humor, an ability to feign interest which made him a hit with women (and he wasn't averse to older, he had a one-night stand with an abstract painter in her fifties who lived at the Chelsea Hotel). He was an expert mixer. Had the connections. Flattered. Pulled his pockets out with seamless timing for a taxi at the end of a night. For he was good company. Thinking of his charm, you miss him, even more than you miss the fifty — I'm sure I'm not the only one who misses him, but I am the narrator, the one who bothers….

Here, now, I see him walking the unknown avenues at midday, watch him snooze at an outdoor café in my Ray-Bans which I lent him and which he returned after staying up all night, good company — unhurried, leisurely — for the feckless and the lonely, see him sneak in a slice of pizza which we split in the same café as on another anonymous prospectless night, introduced politely by him to sketchy French characters unshaven and knit-capped with distrustful darting eyes: like all underground New Yorkers he was an inherently social creature on the lookout for drugs, a free meal, a party, a rave, a house-sitting stint, and he had the New York habit of shopping sidewalk trash; one early morning on a quiet asleep side street with sideglances he lifted a pair of boots a little close for comfort to a stoop. He enjoyed the generosity of the city.

So you, who may be more literal-minded, I hear you ask, at this point, what… how do I owe something to this thief? Well, knowledge. Strange to say, the thief who invades your home (people say they feel "invaded" when burglarized) made me feel more at home in my adopted city. Specifically, when I have a visitor and I am the host and guide, the after-hours places I know about (nestled in unmarked alcoves, faintly illegal) I know about from him. And that essential in-knowledge came from one long fruitful day. It started in the bar where we met, and where I met Tony from whom my mentor subsequently fled. He was broke and I invited him out to breakfast. From midtown meanderingly in the stuporous sunshine we shuffled down to the Lower East Side, an area unknown to me as any arrondissement of Paris. It was probably spring because the shadows were cold, we moved into the sun but we weren't walking fast. I remember we lolled about the hat and scarf stalls on St. Marks and did a bit of bird-watching. After a meal of Dominican beans and rice at a Mexican restaurant (I recall a Puerto Rican mother with a stroller asking us the time) he took me on a tour of the entire Avenue A, including the streets around, pointing out bars, cafés, clubs with an intimate thoroughness unprocurable via the hyped and misleading listings in a publication, tourist or alternative. (One of his scams was entering a nightclub with the excuse to the doorman that we were waiting to talk to a barmaid — what was her name? — then killing time on the vinyl sofas drinkless but in the company of the beautiful foreign girls desultorily looking over the shoulders of their vapid males, until feeling the heat of the extant waitstaff, the chill from the shadow of the bored in-and-out bouncer, we would slink out to case yet another roped-entrance lounge.) On this day, well fed, with no urgent business appointments, he indoctrinated me in the student scene: the juice bars, coffee shops, cheap eateries. Clued me in on the breakfast specials, free refills, buy-backs if he knew the bartender. From that one learning session, intensive yet casual (that was his genius), I was set. Though our bar was still a headquarters, I now had the delicious and necessary freedom of options. My palette had been extended from black and white to a spectrum. The door to the City had been opened (jimmied, kicked in, foot in, how? - did I care?: they're not going to open it to you by any upright, honest, straightforward means).

As for now, the pronounceable yet unspeakable personage with the soiled reputation that cannot be bleached out, infamous, this Cheshire charmer has disappeared. His name handwritten, closeted on a futile forgotten memo. But I will see it and him again in the spiral and labyrinth of the streets. It's just paper after all, these I.O.U.'s that yellow without fire.

David Francis has produced two albums of songs and one of poems. In 2008 BigCityLit published his article "Utterance and Hum: The Difference Between Poem and Song." His stories and poems have appeared in a number of US and UK magazines. http://www.davidfrancismusic.com